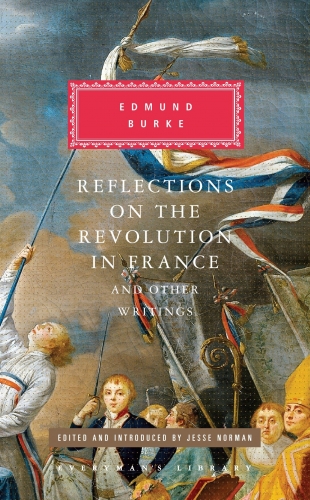

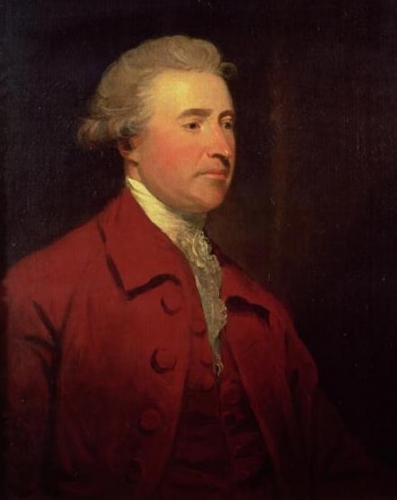

I recently had the pleasure of speaking with Fróði Midjord and Andrew Joyce on Edmund Burke’s classic counter-revolutionary text, Reflections on the Revolution in France. I invite you all to have a listen as Burke’s work, in particular his psychological analysis of the Left, has stood the test of time and remains uncannily insightful in the age of BLM, trans activism, antifa, and all their radical chic apologists.

Burke attacked, with great eloquence, insight, and ferocity, the basic ideas which had emerged in the eighteenth century and still govern our world today: the so-called Rights of Man. For Burke, basing political order on such abstract, ambiguous, and ever-fluctuating ideological fashions could only lead to perpetual chaos culminating yet-more-vicious governments. Instead, he prefers time-tested institutions and customs in tune with human nature.

In terms of practical politics, Burke is in fact quite moderate. One should only cautiously change one’s inherited customs and institutions, always preserving what is valuable. In general, a mixed democratic, aristocratic, and monarchic regime is preferable, but what is actually best will differ according to circumstance (even a democracy might be preferable in some instances). France’s Ancien Régime, he concedes, certainly could be improved upon and capacity for reform is always necessary: “A state without the means of some change is without the means of its conservation” (21). Revolution is an option in the face of a tyrannical government, but it must be the last option, a gamble to be resorted to in exceptionally grave circumstances.

Burkean Community: An Intergenerational Compact

Burke opposes the individualist and egalitarian tendencies of the Enlightenment. His “social contract” is an organic and indeed intergenerational community:

Society is indeed a contract . . . It is a partnership in all science; a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection. As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born. Each contract of each particular state is but a clause in the great primaeval contract of eternal society, linking the lower with the higher natures . . . (96-7)

How sublime is such a vision is as against a politics of maximizing personal choice and fictitious equality!

Society being an intergenerational compact, the current generation must treasure the customs and institutions inherited from the past, which have been patiently built up over the centuries. But let me quote Burke himself:

Through the same plan of a conformity to nature in our artificial institutions, and by calling in the aid of her unerring and powerful instincts, to fortify the fallible and feeble contrivances of our reason, we have derived several other, and those no small benefits, from considering our liberties in the light of an inheritance. (34)

Politicians ought to look to “the practice of their ancestors, the fundamental laws of their country, the fixed form of a constitution, whose merits are confirmed by the solid test of long experience, and an increasing public strength and national prosperity” (58). However, the revolutionaries “despise experience as the wisdom of unlettered men” (58).

Burke’s appeal to intergenerational and inherited wisdom also extends to the personal level in the form a striking defense of prejudice. Prejudice is a concentrate of practical and hard-won wisdom handed down from past generations:

You see, Sir, that in this enlightened age I am bold enough to confess, that we are generally men of untaught feelings; that instead of casting away all our old prejudices, we cherish them to a very considerable degree, and, to take more shame to ourselves, we cherish them because they are prejudices; and the longer they have lasted, and the more generally they have prevailed, the more we cherish them. We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on their own private stock of reason . . . better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations, and of ages. Many of our men of speculation, instead of exploding general prejudices, employ their sagacity to discover the latent wisdom which prevails in them.. Prejudice is of ready application in the emergency; it previously engages the mind in a steady course of wisdom and virtue, and does not leave the man hesitating in the moment of decision, sceptical, puzzled, and unresolved. Prejudice renders a man’s virtue his habit; and not a series of unconnected acts. Through just such prejudice, his duty becomes a part of his nature. (87)

Human Nature as the Foundation of Politics

Burke is emphatic in arguing that political institutions must hew closely to the realities of human nature. He says: “I have endeavoured through my whole life to make myself acquainted with human nature: otherwise I should be unfit to take even my humble part in the service of mankind” (137). He provocatively dismisses the Enlightenment philosophes saying he is “[i]nfluenced by the inborn feelings of my nature . . . not being illuminated by a single ray of this new-sprung modern light” (74).

For Burke, political institutions must not be based on an exaggerated notion of humanity’s capacity for reason, but be carefully adapted to our sentiments: building upon religious piety and ‘irrational’ emotional investment in traditions and institutions, and being careful to not unleash the envy, frustration, and bitterness that lies in every human heart.

Burke is sensitive to the impact of both in-born human nature and upbringing and living conditions in defining men’s character. The ancient lawgivers, he says, “were sensible that the operation of this second nature [upbringing and living conditions] on the first [in-born nature] produced a new combination; and thence arose many diversities among men” (185).

By contrast, the French revolutionaries refused to recognize the diversity of really existing men, but spoke only of “man” in the abstract. Burke lambasts them for being at war with human nature and destroying inherited institutions which bound society together in the name of impossible equality:

[Y]ou think you are combating prejudice, but you are at war with nature. (49)

This sort of people are so taken up with their theories about the rights of man, that they have totally forgot his nature. (64)

[Y]ou ought to make a revolution in nature, and provide a new constitution for the human mind. (202)

Man may not always like his nature, but he only loses by despising and being ignorant of it:

Those who quit their proper character, to assume what does not belong to them, are, for the greater part, ignorant both of the character they leave, and of the character they assume. (11)

You might change the names. The things in some shape must remain. (142)

The Psychology of Egalitarian Revolutionaries

Burke is particularly strong on the psychological mechanisms underlying revolutionary movements. On the moralizing abstract intellectual lacking ‘skin in the game’:

Hypocrisy, of course, delights in the most sublime speculations; for, never intending to go beyond speculation, it costs nothing to have it magnificent. (63)

In fact, insofar revolutionaries have a vested interest, it is in stoking moral outrage:

[V]ices are feigned or exaggerated, when profit is looked for in their punishment. (140)

Burke sees the revolutionaries as destructively critical:

By hating vices too much, they come to love men too little. (171)

A spirit of innovation is generally the result of a selfish temper and confined views. People will not look forward to their posterity, who never look backward to their ancestors. (33)

Paradoxically, a democracy can be more oppressive for dissenters than an autocracy:

Under a cruel prince [dissidents] have the balmy compassion of mankind to assuage the smart of their wounds; they have the plaudits of the people to animate their generous constancy under their sufferings; but those who are subjected to wrong under multitudes, are deprived of all external consolation. They seem deserted by mankind; overpowered by a conspiracy of their whole species (126)

Democratic Intolerance and Revolutionary Chaos

Burke is emphatic in recognizing the intolerant nature of “the rights of man.” He rightly identifies the rights of man as a kind of declaration of war against all other epochs and societies. All eras and places are judged according to the standards of a gathering of Parisian intellectuals circa 1789, and are ever found sorely lacking. The revolutionaries can have no doubts about the righteousness of imposing their views:

They have “the rights of men.” Against these there can be prescription; against these no agreement is binding; these admit no temperament, and no compromise; any thing withheld from their full demand is so much of fraud and injustice. (58)

The upshot of this is that the rights of man are a recipe for perpetual strife and discontent. For those who believe a monarch is legitimate only if elected then “no throne is lawful but the elective, no one act of princes who preceded their aera of fictitious election can be valid” (23). All inherited institutions and customs that violate contemporary moral fashions then become illegitimate and can no longer serve to stabilize and unify society.

But can the revolutionaries not build up something new? Here too, Burke thinks not, because the very revolutionary principles of equality stoke and irritate the desires of men:

[H]appiness . . . is to be found by virtue in all conditions; in which consists the true moral equality of mankind, and not in that monstrous fiction, which, by inspiring false ideas and vain expectations into men destined to travel in the obscure walk of laborious life, serves only to aggravate and embitter the real inequality, which it never can remove . . . (37)

The French armies naturally became insubordinate and fractious, as soldiers demanded to elect their officers and felt no loyalty either to the discredited monarch nor to the Assembly upstarts.

Liberal-Egalitarian Ambiguity and Hypocrisy

The moral intolerance of egalitarian principles then leads to a chaotic radicalization and the revolutionaries one-up each other. To avoid chaos and excess, or simple violation of their interests, the revolutionaries themselves must institute limits on liberty and equality. The hereditary tax privileges attached to the nobility as individuals were abolished, but peasants still had to pay taxes for privileges attached to land, because many bourgeois were such landowners.

The right to vote was conditioned upon a wealth qualification: only men paying taxes worth three days’ labor were eligible, meaning only about 60% of French men could vote. Thus the very poor were excluded from suffrage, not to mention women and inhabitants of the French colonies. Burke snorts with sarcasm:

What! a qualification on the indefeasible right of men? (175)

You lay down metaphysic propositions which infer universal consequences, and then you attempt to limit logic by despotism. (223)

Advocates of the rights of man are universally intolerant of other regimes in the name of these rights, while seeing fit to curtail these rights themselves as the situation requires.

This highlights the basic moral defensiveness of the Right and the universal fervor of the Left. We saw this even in the age of fascism. When a New York Times interviewer criticized Mussolini’s authoritarian regime, the Italian dictator wryly responded: “Democracy is beautiful in theory; in practice it is a fallacy. You in America will see that some day.” Hitler was similarly emphatic, against those Western democrats that feared his ideology, that National Socialism was not for export. Meanwhile, the communists patiently worked according to the principle that all humanity must embrace their system and the liberals drafted documents imposing their own principles on all the nations and races of the Earth.

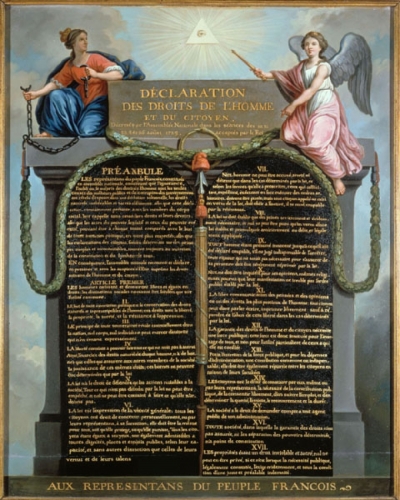

The liberals’ violation in practice of the rights they expound in the abstract is grounded in the very ambiguity of these rights. We cannot accuse the French revolutionaries of too much dishonesty in this respect. In fact, the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen is often shockingly ambiguous. The American Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal,” an observation that, unqualified, is a self-evident falsehood. The French Declaration’s notorious Article I affirms by contrast:

Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions can be founded only on the common good.

One may complain that the latter sentence annihilates the former, but at least it provides a standard for how far rights should extend. In theory, then, even practices of segregation or various hierarchies could be justified if these are considered conducive to “the common good.” The revolutionaries initially did not consider that voting, for instance, was a right, but rather a duty which should only be fulfilled by those best qualified.

Similarly in Article IV’s general provision on liberty:

Liberty consists of doing anything which does not harm others: thus, the exercise of the natural rights of each man has only those borders which assure other members of the society the enjoyment of these same rights. These borders can be determined only by the law.

What “does not harm others”? Does a 70 IQ hereditary idiot fathering 20 children “harm others”? In practice, the reality of universal interdependence annihilates the principle of individual liberty. Today, our liberal democracies regulate every aspect of life, from forcing children to spend years in State education to the hyper-regulation of economic life on redistributive, environmental, and consumer grounds, among many others. Not to mention the massive curtailment of civil liberties and micro-management of citizens’ behavior to fight coronavirus. But, for some reason, our rulers believe that demographic trends, which determine the very character of the nation, should remain wholly unregulated and random.

And Article XI on free speech:

The free communication of thoughts and of opinions is one of the most precious rights of man: any citizen thus may speak, write, print freely, except to respond to the abuse of this liberty, in the cases determined by the law.

The principles may or may not be sound, but they are surely ambiguous and abstract. The United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights by contrast build upon an Anglo-American political and legal tradition, these posit practices (and limits upon them), not merely general principles.

One should not necessarily read too much into the 1789 Declaration. The fundamental points were fairly straightforward: hereditary privileges are abolished, the church must be relegated to a secondary role, sovereignty resides in the nation/people (whatever that means), and the law must rule rather than the king. It’s striking the degree to which later nationalism and indeed fascism took on many of these French revolutionary principles (the Italians quite openly, Mussolini after all started out as a militant socialist atheist).

The revolutionaries of 1789, essentially lawyers and liberals, dreamed of a meritocratic and moderate regime founded on reason: hereditary privileges were abolished, the king was subject to the nation’s representatives and (in theory) the rule of law, and the churchlands were nationalized to shore up government finances. This revolution was achieved partly through the boldness of the men representing the Third Estate but also by periodic and chaotic uprisings of the Paris mob against the state’s forces and even the king himself.

Burke could already see that the precedents and principles the revolutionaries had set could only lead to a chaotic situation spiraling out of control. The unifying institutions of monarchy and church had been dragged through the mud, aristocrats and pious peasants had been turned into enemies, while the hungry Parisian mob, those peasants still smarting from taxation, and the fanatical and paranoid revolutionary elements had not been turned into friends. Thus, said Burke, France could only degenerate into civil war, military dictatorship and an ignoble financial oligarchy: “Here end all the deceitful dreams and visions of the equality and rights of men”! (196)

Burke lamented the end of the European aristocracy:

But the age of chivalry is gone. That of sophisters, economists, and calculators, has succeeded; and the glory of Europe is extinguished forever. Never, never more, shall we behold that generous loyalty to rank and sex, that proud submission, that dignified obedience, that subordination of the heart, which kept alive, even in servitude itself, the spirit of an exalted freedom. (76)

In retrospect, the conflicts of the late eighteenth century can seem rather quaint. From our vantage point, we can see that Britain, America, and France were fundamentally on near-parallel and converging trajectories.

The old constraints and disciplines – the specialization of the sexes, the separation of nations, the very idea of legitimate authority – have steadily disintegrated. Appeal to tradition and religion could no longer sustain them. For a time, from the 1860s to the 1930s or so, it seemed as though Western nations might embrace a biopolitics which, combining old philosophical and new scientific principles, would recognize natural differences and inequalities, thus preserving healthy traditions and indeed healthy progress, tending to biological and cultural perfection.

That tendency stalled and was finally annihilated. Custom, that “tyrant unto man,” has been destroyed in the name of name of the basic principle that humans, “the measure of all things,” are all basically equal and interchangeable atoms. Therefore, our ineradicable social inequalities and specializations can only be the result of our societies’ and cultures’ perversion. We must therefore wage war against our history and our societies – and above all against White men, the great malefactors of humankind.

I cannot help but think that this trend is more driven by a kind of petty self-love, vain and injured amour-propre, than by true self-knowledge, whereby each of us would, with due humility, take up with right pride our particular station in the great chain of being.

There is no telling when and how the current strife will end. On a positive note, Western man’s sensitivity to ‘justice’ as an ideal may lead to perpetual strife, but is also clearly a great source of the experimentation and dynamism which characterizes our history. In Europe, the state is smoothly leading the totalitarian march towards the mirage of equality. In America, there is chaos and neither history, nor culture, nor race, nor anything else seems to keep that great landmass-cum-economic zone together. What will be the new equilibrium and when will it arise? Will the liberals, holding true to their ideals over inconvenient facts, completely wreck their own cities? Will the regime stabilize under a Biden presidency tending towards European-style social-democracy? When will meet our Bonaparte?

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

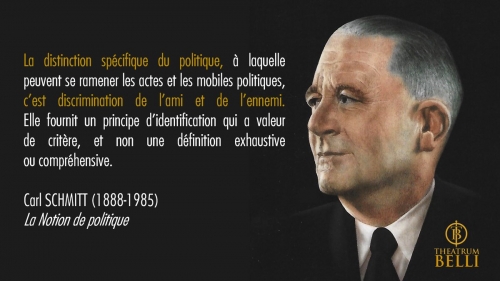

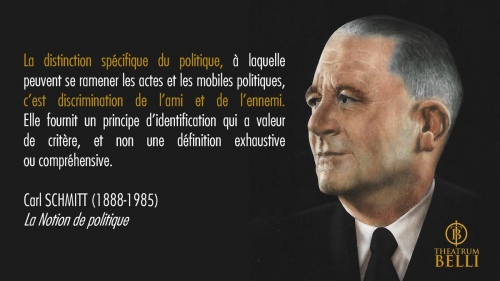

Like many of his books, Carl Schmitt’s The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923) is a slender volume packed with explosive ideas.

Like many of his books, Carl Schmitt’s The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy (1923) is a slender volume packed with explosive ideas. The rationale for making decisions in parliament, as opposed to reposing them in the hands of a single man, is that even the wisest man may benefit from hearing other points of view. We are more likely to arrive at the best possible decision if a number of people bring different perspectives and bodies of knowledge to the table. But the process only works if all parties are open to being persuaded by one another, i.e., they are willing to change their minds if they hear a better argument. This is what argument in “good faith” means, as opposed to merely shilling for a fixed idea.

The rationale for making decisions in parliament, as opposed to reposing them in the hands of a single man, is that even the wisest man may benefit from hearing other points of view. We are more likely to arrive at the best possible decision if a number of people bring different perspectives and bodies of knowledge to the table. But the process only works if all parties are open to being persuaded by one another, i.e., they are willing to change their minds if they hear a better argument. This is what argument in “good faith” means, as opposed to merely shilling for a fixed idea. Liberalism’s abstract egalitarian zeal has never resulted in a global liberal democracy or the enfranchisement of every infant or imbecile (p. 16). Indeed, such goals are impossible. But it has undermined the conditions that make good-faith parliamentary discussions possible.

Liberalism’s abstract egalitarian zeal has never resulted in a global liberal democracy or the enfranchisement of every infant or imbecile (p. 16). Indeed, such goals are impossible. But it has undermined the conditions that make good-faith parliamentary discussions possible. Schmitt isn’t always forthcoming about his own political preferences, but sometimes his rhetoric tips his hand. The first three chapters of Crisis are quite dry, and Schmitt’s arguments only really come into focus in the 1926 Preface to the Second Edition. But chapter 4 crackles with enthusiasm as Schmitt discusses Sorel’s Reflections on Violence, as well as Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Spanish Catholic reactionary Juan Donoso Cortés. Then Schmitt ends by arguing that nationalism and fascism are more consistent with Sorel’s ultimate premises than are Communism, socialism, or anarcho-syndicalism.

Schmitt isn’t always forthcoming about his own political preferences, but sometimes his rhetoric tips his hand. The first three chapters of Crisis are quite dry, and Schmitt’s arguments only really come into focus in the 1926 Preface to the Second Edition. But chapter 4 crackles with enthusiasm as Schmitt discusses Sorel’s Reflections on Violence, as well as Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, and Spanish Catholic reactionary Juan Donoso Cortés. Then Schmitt ends by arguing that nationalism and fascism are more consistent with Sorel’s ultimate premises than are Communism, socialism, or anarcho-syndicalism. Schmitt then hastens to add that a similar vision of a bloody final reckoning was found on the Right: “In 1848 this image rose up on both sides in opposition to parliamentary constitutionalism: from the side of tradition in a conservative sense, represented by a Catholic Spaniard, Donoso Cortés, and in radical anarcho-syndicalism in Proudhon. Both demanded a decision. . . . Instead of relative oppositions accessible to parliamentary means, absolute antitheses now appear” (p. 69). But the tireless talk of bourgeois parliamentarians is all about evading the necessity of decision in the face of hard either/ors, about evading the existence of real enmity. “In the eyes of Donoso Cortés, this socialist anarchist [Proudhon] was an evil demon, a devil, and for Proudhon the Catholic was a fanatical Grand Inquisitor, whom he attempted to laugh off. Today it is easy to see that both were their own real opponent and that everything else was only a provisional half-measure” (p. 70). Schmitt clearly hungers for a similar clarity in Weimar and saw the rise of Fascism in Italy as the present-day nemesis of the Left.

Schmitt then hastens to add that a similar vision of a bloody final reckoning was found on the Right: “In 1848 this image rose up on both sides in opposition to parliamentary constitutionalism: from the side of tradition in a conservative sense, represented by a Catholic Spaniard, Donoso Cortés, and in radical anarcho-syndicalism in Proudhon. Both demanded a decision. . . . Instead of relative oppositions accessible to parliamentary means, absolute antitheses now appear” (p. 69). But the tireless talk of bourgeois parliamentarians is all about evading the necessity of decision in the face of hard either/ors, about evading the existence of real enmity. “In the eyes of Donoso Cortés, this socialist anarchist [Proudhon] was an evil demon, a devil, and for Proudhon the Catholic was a fanatical Grand Inquisitor, whom he attempted to laugh off. Today it is easy to see that both were their own real opponent and that everything else was only a provisional half-measure” (p. 70). Schmitt clearly hungers for a similar clarity in Weimar and saw the rise of Fascism in Italy as the present-day nemesis of the Left. Schmitt closes with an immanent critique of Sorel. First, Schmitt argues that Sorel himself ultimately subordinates proletarian myth and violence to rationalism, because the goal of the revolution is to take control of the means of production. But the modern economic system is of a piece with bourgeois democracy, thus “If one followed the bourgeois into economic terrain, then one must also follow him into democracy and parliamentarism” (p. 73). This does not strike me as particularly persuasive. When Schmitt was writing, the example of Imperial Japan showed that one can have a modern industrial economy without liberal democracy.

Schmitt closes with an immanent critique of Sorel. First, Schmitt argues that Sorel himself ultimately subordinates proletarian myth and violence to rationalism, because the goal of the revolution is to take control of the means of production. But the modern economic system is of a piece with bourgeois democracy, thus “If one followed the bourgeois into economic terrain, then one must also follow him into democracy and parliamentarism” (p. 73). This does not strike me as particularly persuasive. When Schmitt was writing, the example of Imperial Japan showed that one can have a modern industrial economy without liberal democracy. The nineteenth century was the age of parliamentary liberal democracy. The twentieth century is the age of political myths. The rise of political myth is itself “the most powerful symptom of the decline of the relative rationalism of parliamentary thought” (p. 76). The Left may be the gravedigger of liberal democracy, but it offers no real alternative, simply modern materialism and rationalism stripped of the liberal charms of freedom and private life.

The nineteenth century was the age of parliamentary liberal democracy. The twentieth century is the age of political myths. The rise of political myth is itself “the most powerful symptom of the decline of the relative rationalism of parliamentary thought” (p. 76). The Left may be the gravedigger of liberal democracy, but it offers no real alternative, simply modern materialism and rationalism stripped of the liberal charms of freedom and private life.

Il y a longtemps qu’Augustin Cochin avait exposé sa théorie de la confiscation des pouvoirs dans nos modernes démocraties, républiques ou autres nations unies. Cochin expliquait pourquoi ce sont toujours « eux » qui décident et pas « nous » ; on est en 1793, quand les sociétés de pensée ont décidé de refaire l’Homme, la Femme, la France, l’Humanité, le reste. Le triste programme de tabula rasa et de refonte est toujours le même depuis cette époque, dirigé par une élite implacable, conspiratrice et motivée :

Il y a longtemps qu’Augustin Cochin avait exposé sa théorie de la confiscation des pouvoirs dans nos modernes démocraties, républiques ou autres nations unies. Cochin expliquait pourquoi ce sont toujours « eux » qui décident et pas « nous » ; on est en 1793, quand les sociétés de pensée ont décidé de refaire l’Homme, la Femme, la France, l’Humanité, le reste. Le triste programme de tabula rasa et de refonte est toujours le même depuis cette époque, dirigé par une élite implacable, conspiratrice et motivée : Mais Cochin distingue la méthode. Tout est dans la méthode. Et à propos de la Révolution :

Mais Cochin distingue la méthode. Tout est dans la méthode. Et à propos de la Révolution : Cochin précise ensuite que nos utopistes, que nos idéalistes sont dangereux parce qu’ils ne sont pas utopistes précisément. Et il se réclame bien sûr des Grecs (Cité/Polis/Politique), d’Aristophane, de sa satire des mœurs démocratiques athéniennes :

Cochin précise ensuite que nos utopistes, que nos idéalistes sont dangereux parce qu’ils ne sont pas utopistes précisément. Et il se réclame bien sûr des Grecs (Cité/Polis/Politique), d’Aristophane, de sa satire des mœurs démocratiques athéniennes : Puis Cochin s’inspire d’Ostrogorski pour écrire les lignes suivantes :

Puis Cochin s’inspire d’Ostrogorski pour écrire les lignes suivantes : Et voilà pourquoi la machine préfère à toutes les autres les activités malsaines, fiévreuses et stériles, impropres, par nature et par elles-mêmes, à la vie normale. Celles-là seulement ne peuvent être qu’impersonnelles. Un viveur qui dissipe ce qu’il vole : voilà ce qui convient en fait de concussion. »

Et voilà pourquoi la machine préfère à toutes les autres les activités malsaines, fiévreuses et stériles, impropres, par nature et par elles-mêmes, à la vie normale. Celles-là seulement ne peuvent être qu’impersonnelles. Un viveur qui dissipe ce qu’il vole : voilà ce qui convient en fait de concussion. »

La menace à l'ordre social a été perçue autrefois, comme une des réponses à la "Révolte des masses"(Ortega y Gasset - 1930). Cette menace, venant de la social- démocratie, du marxisme théorique et de la révolution russe, fut à la racine d'une réflexion, sur la théorie des élites, représentée, autour des années 1920, par Pareto, Mosca et Michels, en réponse au dysfonctionnement du régime libéral et de son système parlementaire.

La menace à l'ordre social a été perçue autrefois, comme une des réponses à la "Révolte des masses"(Ortega y Gasset - 1930). Cette menace, venant de la social- démocratie, du marxisme théorique et de la révolution russe, fut à la racine d'une réflexion, sur la théorie des élites, représentée, autour des années 1920, par Pareto, Mosca et Michels, en réponse au dysfonctionnement du régime libéral et de son système parlementaire. En effet une époque s'achève, celle du rationalisme moderne, matérialiste, technocratique et instrumental, qui avait perdu sa relation au "sens" de la vie et au tragique, la mort, conduisant à la finitude de l'aventure humaine, imbue du destin et des valeurs ancestrales.

En effet une époque s'achève, celle du rationalisme moderne, matérialiste, technocratique et instrumental, qui avait perdu sa relation au "sens" de la vie et au tragique, la mort, conduisant à la finitude de l'aventure humaine, imbue du destin et des valeurs ancestrales.

Professor Johnson’s academic work is dedicated to the delegitimization of the global capitalist system and the demystification of the ideology that justifies it. This is a demonic, serpentine Leviathan spreading the postmodern acid of American-sponsored mass-zombification to the world.

Professor Johnson’s academic work is dedicated to the delegitimization of the global capitalist system and the demystification of the ideology that justifies it. This is a demonic, serpentine Leviathan spreading the postmodern acid of American-sponsored mass-zombification to the world.

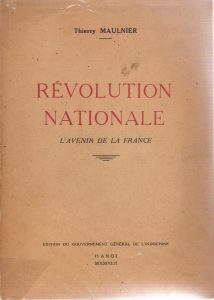

Thierry Maulnier, nom de plume de Jacques Louis André Talagrand (1909 – 1988), a rédigé de nombreux essais, écrit plusieurs pièces de théâtre et donné bien des préfaces. Sa bibliographie comporte cependant une omission de taille : l’absence de Révolution Nationale. L’avenir de la France. Cet ouvrage s’apparente à une sorte de fantôme dont diverses personnes ont nié son existence réelle.

Thierry Maulnier, nom de plume de Jacques Louis André Talagrand (1909 – 1988), a rédigé de nombreux essais, écrit plusieurs pièces de théâtre et donné bien des préfaces. Sa bibliographie comporte cependant une omission de taille : l’absence de Révolution Nationale. L’avenir de la France. Cet ouvrage s’apparente à une sorte de fantôme dont diverses personnes ont nié son existence réelle. Cette hypothèse expliquerait la non reconnaissance de cette édition par Thierry Maulnier d’autant que la même année sort chez Lardanchet La France la guerre et la paix. Dans cet autre recueil, voulu celui-ci par Maulnier, se trouvent trois textes présents dans Révolution Nationale : « Guerre mondiale et Révolution nationale » à l’identique dans les deux ouvrages tandis que les premiers paragraphes de « Rester la France » et « La médiation française » ont été réécrits pour cette parution. Dès la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Thierry Maulnier publie chez Gallimard Violence et Conscience qui « a été écrit en 1942 et 1943 (p. 1) » et qui contient une version modifiée et enrichie à partir du deuxième paragraphe de « Révolution prolétarienne et réaction patriarcale ». En 1946, chez un jeune éditeur moins consensuel, La Table Ronde, paraît Arrière-pensées qui réunit des chroniques « écrites et publiées entre le printemps de 1941 et le printemps de 1944 (p. 5) ». Par rapport à Révolution Nationale, on relit souvent dans une version modifiée, voire changée, « Les poseurs de rails », « Avant l’assaut », « Erreurs de jeunesse », « L’assaut des médiocres », « Les “ intellectuels ” sont-ils responsables du désastre ? », « Un jugement sur Racine », « L’art et l’éducation », « Polémique d’ancien régime » et « L’esprit français est-il coupable ? » qui s’intitule dans Révolution Nationale « Controverses sur l’esprit français » (1). On suppose que les textes qui forment Révolution Nationale proviennent directement des périodiques. Dans le cas des recueils autorisés, Thierry Maulnier a retravaillé certains passages afin de les lier aux autres textes et d’en donner une cohérence interne évidente.

Cette hypothèse expliquerait la non reconnaissance de cette édition par Thierry Maulnier d’autant que la même année sort chez Lardanchet La France la guerre et la paix. Dans cet autre recueil, voulu celui-ci par Maulnier, se trouvent trois textes présents dans Révolution Nationale : « Guerre mondiale et Révolution nationale » à l’identique dans les deux ouvrages tandis que les premiers paragraphes de « Rester la France » et « La médiation française » ont été réécrits pour cette parution. Dès la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Thierry Maulnier publie chez Gallimard Violence et Conscience qui « a été écrit en 1942 et 1943 (p. 1) » et qui contient une version modifiée et enrichie à partir du deuxième paragraphe de « Révolution prolétarienne et réaction patriarcale ». En 1946, chez un jeune éditeur moins consensuel, La Table Ronde, paraît Arrière-pensées qui réunit des chroniques « écrites et publiées entre le printemps de 1941 et le printemps de 1944 (p. 5) ». Par rapport à Révolution Nationale, on relit souvent dans une version modifiée, voire changée, « Les poseurs de rails », « Avant l’assaut », « Erreurs de jeunesse », « L’assaut des médiocres », « Les “ intellectuels ” sont-ils responsables du désastre ? », « Un jugement sur Racine », « L’art et l’éducation », « Polémique d’ancien régime » et « L’esprit français est-il coupable ? » qui s’intitule dans Révolution Nationale « Controverses sur l’esprit français » (1). On suppose que les textes qui forment Révolution Nationale proviennent directement des périodiques. Dans le cas des recueils autorisés, Thierry Maulnier a retravaillé certains passages afin de les lier aux autres textes et d’en donner une cohérence interne évidente. En outre, « le destin de la Révolution nationale, poursuit-il, est précisément de ne se laisser attirer ni par l’ancienne gauche, ni par l’ancienne droite : d’attirer au contraire en elle l’ancienne gauche et l’ancienne droite pour abolir en elles leurs stériles contradictions et pour les anéantir (p. 82) ». Voilà pourquoi « c’est dans la révolution nationale et dans la révolution nationale seule que la France peut aujourd’hui trouver les moyens de guérir ou plutôt de renaître, faire éclater la vigueur d’un génie qui survit intact à ses blessures, affirmer son droit à la vie (pp. 76 – 77) ». Il devient évident que « c’est sur nous et nous seuls que nous devons compter pour créer une civilisation où il nous soit possible de vivre (p. 55) ».

En outre, « le destin de la Révolution nationale, poursuit-il, est précisément de ne se laisser attirer ni par l’ancienne gauche, ni par l’ancienne droite : d’attirer au contraire en elle l’ancienne gauche et l’ancienne droite pour abolir en elles leurs stériles contradictions et pour les anéantir (p. 82) ». Voilà pourquoi « c’est dans la révolution nationale et dans la révolution nationale seule que la France peut aujourd’hui trouver les moyens de guérir ou plutôt de renaître, faire éclater la vigueur d’un génie qui survit intact à ses blessures, affirmer son droit à la vie (pp. 76 – 77) ». Il devient évident que « c’est sur nous et nous seuls que nous devons compter pour créer une civilisation où il nous soit possible de vivre (p. 55) ». Thierry Maulnier conçoit la Révolution Nationale, on l’a vu, comme la matrice d’un nouvel ordre français. « Il faut créer de nouvelles mœurs, de nouvelles valeurs et de nouveaux modes de pensée (p. 71). » Comment ? Ce qu’il propose convient au fonctionnaire de la propagande à Hanoï qui a classé les textes à sa disposition. « refaire une nation, c’est d’abord se donner les moyens de la refaire. C’est d’abord occuper et réorganiser l’État (p. 22). » l’auteur s’intéresse aux interactions psychiques, sociales et politiques entre le « Chef », l’élite et le peuple. « La nature de l’autorité n’est pas seulement d’accroître la force ou pour mieux dire l’efficacité de ceux qui lui obéissent; elle est de métamorphoser cette force en une force de qualité supérieure (p. 204). » Cependant, « l’autorité elle-même, pour atteindre à toute sa vertu, a besoin à son tour de la collaboration de ceux sur qui elle s’exerce. Elle perd beaucoup de son efficacité, s’il ne lui est donné qu’une obéissance passive et comme inerte (p. 205) ». Cela signifie restaurer ce qui est à l’origine de la nation française : l’État. « C’est le pouvoir qui devait donc être rétabli ou refait avant toute chose : c’est l’ensemble des moyens d’exécution; c’est l’État. C’est par l’État que la reconstruction française à commencer (p. 23). »

Thierry Maulnier conçoit la Révolution Nationale, on l’a vu, comme la matrice d’un nouvel ordre français. « Il faut créer de nouvelles mœurs, de nouvelles valeurs et de nouveaux modes de pensée (p. 71). » Comment ? Ce qu’il propose convient au fonctionnaire de la propagande à Hanoï qui a classé les textes à sa disposition. « refaire une nation, c’est d’abord se donner les moyens de la refaire. C’est d’abord occuper et réorganiser l’État (p. 22). » l’auteur s’intéresse aux interactions psychiques, sociales et politiques entre le « Chef », l’élite et le peuple. « La nature de l’autorité n’est pas seulement d’accroître la force ou pour mieux dire l’efficacité de ceux qui lui obéissent; elle est de métamorphoser cette force en une force de qualité supérieure (p. 204). » Cependant, « l’autorité elle-même, pour atteindre à toute sa vertu, a besoin à son tour de la collaboration de ceux sur qui elle s’exerce. Elle perd beaucoup de son efficacité, s’il ne lui est donné qu’une obéissance passive et comme inerte (p. 205) ». Cela signifie restaurer ce qui est à l’origine de la nation française : l’État. « C’est le pouvoir qui devait donc être rétabli ou refait avant toute chose : c’est l’ensemble des moyens d’exécution; c’est l’État. C’est par l’État que la reconstruction française à commencer (p. 23). »

![La_face_de_Méduse_du_[...]Maulnier_Thierry_bpt6k3355720d.JPEG](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/01/00/1643598651.JPEG) La Révolution Nationale doit de facto « dès maintenant nous préparer à une paix qui pourrait être pour nous, sin nous n’y prenons garde, plus redoutable que la guerre elle-même (p. 44) ». Il lui assigne donc une tâche ardue : fondre toutes les contradictions nationales dans un seul môle. En effet, « le drame du monde moderne vient de ce que les valeurs dont la composition merveilleuse et l’équilibre sans cesse en mouvement font une société harmonieuse ont commencé de se séparer les unes des autres, de s’exclure les unes les autres avec une fanatique intolérance, de s’amplifier jusqu’au mythe et d’exercer leur ravage anarchique en visant d’une vie monstrueusement indépendante (pp. 52 – 53) ». D’où cette mentalité française qui s’installe facilement dans la routine. « Si les Français se sont montrés inférieurs à d’autres peuples, au cours des cinquante dernières années, ce n’est pas dans la vitalité, ce n’est pas dans le jaillissement des sources créatrices, c’est dans l’organisation, l’utilisation, l’exploitation de leurs ressources. Ils n’ont pas été dépassés dans l’ordre de l’invention scientifique, mais dans celui des applications industrielles (p. 11) ». Il ne pointe pourtant pas la cause pratique de ces échecs répétés : une administration de plus en plus bureaucratique qui freine ou noie toute initiative originale afin de rester dans un moule normatif confortable. Il n’entend pas que la Révolution Nationale s’affadisse ou s’embourbe dans le marais des ministères incapables de se faire obéir de ses fonctionnaires.

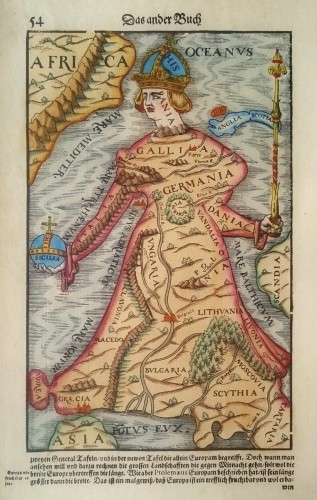

La Révolution Nationale doit de facto « dès maintenant nous préparer à une paix qui pourrait être pour nous, sin nous n’y prenons garde, plus redoutable que la guerre elle-même (p. 44) ». Il lui assigne donc une tâche ardue : fondre toutes les contradictions nationales dans un seul môle. En effet, « le drame du monde moderne vient de ce que les valeurs dont la composition merveilleuse et l’équilibre sans cesse en mouvement font une société harmonieuse ont commencé de se séparer les unes des autres, de s’exclure les unes les autres avec une fanatique intolérance, de s’amplifier jusqu’au mythe et d’exercer leur ravage anarchique en visant d’une vie monstrueusement indépendante (pp. 52 – 53) ». D’où cette mentalité française qui s’installe facilement dans la routine. « Si les Français se sont montrés inférieurs à d’autres peuples, au cours des cinquante dernières années, ce n’est pas dans la vitalité, ce n’est pas dans le jaillissement des sources créatrices, c’est dans l’organisation, l’utilisation, l’exploitation de leurs ressources. Ils n’ont pas été dépassés dans l’ordre de l’invention scientifique, mais dans celui des applications industrielles (p. 11) ». Il ne pointe pourtant pas la cause pratique de ces échecs répétés : une administration de plus en plus bureaucratique qui freine ou noie toute initiative originale afin de rester dans un moule normatif confortable. Il n’entend pas que la Révolution Nationale s’affadisse ou s’embourbe dans le marais des ministères incapables de se faire obéir de ses fonctionnaires. Thierry Maulnier pense par conséquent que « la France n’est pas le pays de la mesure : mais elle est, géographiquement, historiquement, socialement, moralement, intellectuellement, le pays de la conciliation des contraires (p. 59) ». Malgré la Débâcle de 1940, le pays vaincu conserve des atouts. Ceux-ci reposent sur sa géographie. L’auteur se lance dans une succincte et pertinente analyse géopolitique qui bouscule la fameuse et sempiternelle dualité Terre – Mer. La « complexité de notre civilisation nous est imposée par notre sol lui-même. Solidement établie au cœur de l’Europe, la France regarde en même temps vers toutes mers, et la géographie l’attache en même temps aux peuples continentaux et aux peuples maritimes qui se disputent en ce moment la prééminence. L’Allemagne n’est qu’européenne (6), l’Angleterre n’est qu’impériale (7) : la France est européenne et impériale en même temps. On en a vu les conséquences dans l’histoire militaire : celle de l’Allemagne n’est guère que terrestre, celle de l’Angleterre n’est guère que marine. Tout au long de son histoire, la France a dû se battre sur terre et sur mer en même temps (pp. 60 – 61) ». Encore de nos jours, l’Hexagone républicain se voit tiraillé entre un projet pseudo-européen germanocentré sous la houlette étatsunienne, une francophonie « grand remplaciste » métisseuse mondialisée et un monde atlantique anglo-saxon auquel il se rattache indirectement par la Normandie et la rémanence territoriale de la Grande Louisiane et de la Nouvelle-France des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles… Terre de contrastes majeurs parce que « continentale et maritime, agricole et urbaine, européenne et impériale, nationaliste et humaniste, unitaire et régionaliste, religieux et rationaliste (8), particulariste et cosmopolite, pacifique et guerrière, la France concentre en elle toutes les contradictions de l’univers et a fait sa civilisation et sa vie, passablement heureuse et glorieuse au cours des siècles, de ces mêmes contradictions (p. 65) ».

Thierry Maulnier pense par conséquent que « la France n’est pas le pays de la mesure : mais elle est, géographiquement, historiquement, socialement, moralement, intellectuellement, le pays de la conciliation des contraires (p. 59) ». Malgré la Débâcle de 1940, le pays vaincu conserve des atouts. Ceux-ci reposent sur sa géographie. L’auteur se lance dans une succincte et pertinente analyse géopolitique qui bouscule la fameuse et sempiternelle dualité Terre – Mer. La « complexité de notre civilisation nous est imposée par notre sol lui-même. Solidement établie au cœur de l’Europe, la France regarde en même temps vers toutes mers, et la géographie l’attache en même temps aux peuples continentaux et aux peuples maritimes qui se disputent en ce moment la prééminence. L’Allemagne n’est qu’européenne (6), l’Angleterre n’est qu’impériale (7) : la France est européenne et impériale en même temps. On en a vu les conséquences dans l’histoire militaire : celle de l’Allemagne n’est guère que terrestre, celle de l’Angleterre n’est guère que marine. Tout au long de son histoire, la France a dû se battre sur terre et sur mer en même temps (pp. 60 – 61) ». Encore de nos jours, l’Hexagone républicain se voit tiraillé entre un projet pseudo-européen germanocentré sous la houlette étatsunienne, une francophonie « grand remplaciste » métisseuse mondialisée et un monde atlantique anglo-saxon auquel il se rattache indirectement par la Normandie et la rémanence territoriale de la Grande Louisiane et de la Nouvelle-France des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles… Terre de contrastes majeurs parce que « continentale et maritime, agricole et urbaine, européenne et impériale, nationaliste et humaniste, unitaire et régionaliste, religieux et rationaliste (8), particulariste et cosmopolite, pacifique et guerrière, la France concentre en elle toutes les contradictions de l’univers et a fait sa civilisation et sa vie, passablement heureuse et glorieuse au cours des siècles, de ces mêmes contradictions (p. 65) ». Espérant que « la structure économique de la France de demain sera corporative (p. 119) », Thierry Maulnier se plaît à souligner au nom d’une future et éventuelle convergence des révolutionnaires nationaux de « droite » et des révolutionnaires sociaux de « gauche » que « l’opposition légitimiste approuva les révoltes ouvrières contre la monarchie bourgeoise et libérale de Louis-Philippe (p. 121) ». Parce que « la Révolution Nationale n’est pas le régime de la facilité : elle demande et doit demander à chacun la patience dans l’effort et le sacrifice (p. 139) », son rôle « est précisément d’arracher le travail à cette dégradation qu’il subit dans l’exploitation capitaliste et dans les réactions qu’elle provoque (p. 137) » en s’appuyant sur un corporatisme renaissant à expérimenter. Il est clair qu’« anticapitaliste, [la Révolution Nationale] ne se confond ni avec la réaction patriarcale ni avec la révolution prolétarienne. […] Elle est la révolution d’une société qui ne se renie pas pas, mais obéit à sa loi interne d’un présent qui ne transforme le passé que pour l’accomplir (pp. 124 – 125) ». N’est-ce pas la définition exacte d’une révolution conservatrice ?

Espérant que « la structure économique de la France de demain sera corporative (p. 119) », Thierry Maulnier se plaît à souligner au nom d’une future et éventuelle convergence des révolutionnaires nationaux de « droite » et des révolutionnaires sociaux de « gauche » que « l’opposition légitimiste approuva les révoltes ouvrières contre la monarchie bourgeoise et libérale de Louis-Philippe (p. 121) ». Parce que « la Révolution Nationale n’est pas le régime de la facilité : elle demande et doit demander à chacun la patience dans l’effort et le sacrifice (p. 139) », son rôle « est précisément d’arracher le travail à cette dégradation qu’il subit dans l’exploitation capitaliste et dans les réactions qu’elle provoque (p. 137) » en s’appuyant sur un corporatisme renaissant à expérimenter. Il est clair qu’« anticapitaliste, [la Révolution Nationale] ne se confond ni avec la réaction patriarcale ni avec la révolution prolétarienne. […] Elle est la révolution d’une société qui ne se renie pas pas, mais obéit à sa loi interne d’un présent qui ne transforme le passé que pour l’accomplir (pp. 124 – 125) ». N’est-ce pas la définition exacte d’une révolution conservatrice ?

L’année 1968 sera marquée par un enchaînement de révoltes partout sur le globe : dans le camp occidental, des États-Unis au Japon, en passant par la France ou l’Italie mais aussi dans certains pays du pacte de Varsovie, comme en Pologne ou en Tchécoslovaquie. L’ensemble de l’ordre du monde bipolaire capital-communiste issu de Yalta et du tribunal de Nuremberg allait être ainsi traversé dans un même élan par une série de révoltes marquées par le choc des générations. Pourtant, l’irruption soudaine de cette contestation étudiante internationale n’était pas le fruit du hasard mais bien celui d’un long travail d’incubation intellectuel et politique commencé il y a plusieurs décennies et qui connaîtrait son paroxysme dans les années d’après-guerre. Comme si des forces trop longtemps contenues et désormais sans frein se frayaient maintenant un chemin vers la surface et chercher à tout emporter avec l’éclatante et audacieuse énergie de la jeunesse. Les forces de l’ « Eros » déchaînées, chères aux théoriciens du freudo-marxisme.

L’année 1968 sera marquée par un enchaînement de révoltes partout sur le globe : dans le camp occidental, des États-Unis au Japon, en passant par la France ou l’Italie mais aussi dans certains pays du pacte de Varsovie, comme en Pologne ou en Tchécoslovaquie. L’ensemble de l’ordre du monde bipolaire capital-communiste issu de Yalta et du tribunal de Nuremberg allait être ainsi traversé dans un même élan par une série de révoltes marquées par le choc des générations. Pourtant, l’irruption soudaine de cette contestation étudiante internationale n’était pas le fruit du hasard mais bien celui d’un long travail d’incubation intellectuel et politique commencé il y a plusieurs décennies et qui connaîtrait son paroxysme dans les années d’après-guerre. Comme si des forces trop longtemps contenues et désormais sans frein se frayaient maintenant un chemin vers la surface et chercher à tout emporter avec l’éclatante et audacieuse énergie de la jeunesse. Les forces de l’ « Eros » déchaînées, chères aux théoriciens du freudo-marxisme.

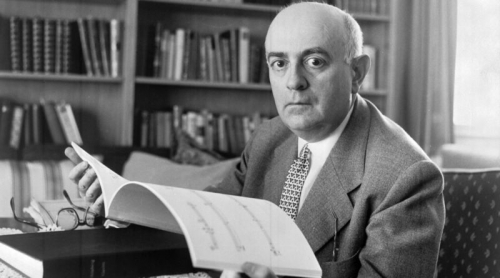

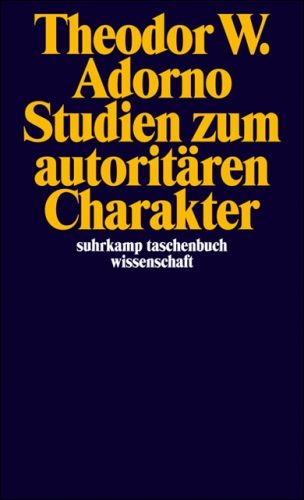

Relire aujourd’hui les Études sur la personnalité autoritaire de Theodor W. Adorno et de l’Institut de Recherche Social se révèle très instructif pour comprendre d’où provient une grande partie du mal-être et de la mauvaise conscience qui mine l’Occident contemporain. On y découvre l’application méthodique et clinique de penseurs politiques engagés qui se sont arrogés le droit de déterminer ce qui est moral ou non, non seulement dans l’Histoire et la culture de l’Occident mais jusque dans l’inconscient supposé des populations occidentales afin de l’en extirper comme par un acte psycho-chirurgical.

Relire aujourd’hui les Études sur la personnalité autoritaire de Theodor W. Adorno et de l’Institut de Recherche Social se révèle très instructif pour comprendre d’où provient une grande partie du mal-être et de la mauvaise conscience qui mine l’Occident contemporain. On y découvre l’application méthodique et clinique de penseurs politiques engagés qui se sont arrogés le droit de déterminer ce qui est moral ou non, non seulement dans l’Histoire et la culture de l’Occident mais jusque dans l’inconscient supposé des populations occidentales afin de l’en extirper comme par un acte psycho-chirurgical.

On sait que ces « valeurs », que l’on dit découler de la nature humaine, en fait, plus certainement, des délires philosophistes du XVIIIe siècle, sont celles qui charpentent le « pacte républicain », contrat social de la République dite « française ». Grâce au contrat social, ou pacte républicain, une société peut s’organiser et fonctionner avec des hommes venus du monde entier puisque les valeurs et principes qui président à cette organisation et à ce fonctionnement découlent de l’universelle nature humaine, et non de telle ou telle culture particulière. Ainsi une société fondée sur les droits naturels de l’Homme (le droit à la liberté, à l’égalité, à la propriété) serait acceptable par tous puisque ne contredisant les aspirations essentielles d’aucun. Les joueurs de pipo avaient simplement oublié de définir ce qu’on entendait par « liberté », « égalité » ou « propriété »…

On sait que ces « valeurs », que l’on dit découler de la nature humaine, en fait, plus certainement, des délires philosophistes du XVIIIe siècle, sont celles qui charpentent le « pacte républicain », contrat social de la République dite « française ». Grâce au contrat social, ou pacte républicain, une société peut s’organiser et fonctionner avec des hommes venus du monde entier puisque les valeurs et principes qui président à cette organisation et à ce fonctionnement découlent de l’universelle nature humaine, et non de telle ou telle culture particulière. Ainsi une société fondée sur les droits naturels de l’Homme (le droit à la liberté, à l’égalité, à la propriété) serait acceptable par tous puisque ne contredisant les aspirations essentielles d’aucun. Les joueurs de pipo avaient simplement oublié de définir ce qu’on entendait par « liberté », « égalité » ou « propriété »…

À tout moment et dans toute conjoncture; l'homme est acculé à un choix. Par ce choix, il affirme sa vocation profonde qui confère au projet humain la portée d'un engagement, dans lequel l'individu risque la perte de son existence et celle de son âme.

À tout moment et dans toute conjoncture; l'homme est acculé à un choix. Par ce choix, il affirme sa vocation profonde qui confère au projet humain la portée d'un engagement, dans lequel l'individu risque la perte de son existence et celle de son âme. Vers 1860, Dilthey, considéré par Ortega y Gasset comme le plus grand penseur de la deuxième moitié du dix-neuvième siècle, fit la découverte d'une nouvelle réalité philosophique, celle de la « vie humaine ». La vie, rappelle ce dernier, n'est point « quelque chose de dérivé ou de secondaire, mais le constituant de l'idée elle-même ».

Vers 1860, Dilthey, considéré par Ortega y Gasset comme le plus grand penseur de la deuxième moitié du dix-neuvième siècle, fit la découverte d'une nouvelle réalité philosophique, celle de la « vie humaine ». La vie, rappelle ce dernier, n'est point « quelque chose de dérivé ou de secondaire, mais le constituant de l'idée elle-même ». L'ère révolutionnaire, dans laquelle la politique se trouvait au centre des inquiétudes humaines », où la politisation intégrale de la vie avait atteint son apogée, cette période de ferveur intense est révolue. Elle représentait une évidente aberration de la perspective sentimentale, car « l'homme moderne, qui a montré sa poitrine sur les barricades de la révolution, a montré sans équivoque qu'il attendait la félicité de la politique ».

L'ère révolutionnaire, dans laquelle la politique se trouvait au centre des inquiétudes humaines », où la politisation intégrale de la vie avait atteint son apogée, cette période de ferveur intense est révolue. Elle représentait une évidente aberration de la perspective sentimentale, car « l'homme moderne, qui a montré sa poitrine sur les barricades de la révolution, a montré sans équivoque qu'il attendait la félicité de la politique ». Immédiatement, nous observons la fin provisoire de l'âge idéologique et de l'utilisation, bonne ou mauvaise, de celle-ci. Cela ne signifie point leur disparition définitive, car les utopies et les rêves réapparais-sent perpétuellement dans le siècle, et ils en constituent la trame imaginaire. Les sociétés développées ont refusé le fanatisme et le millénarisme, au profit d'une phase d'apaisement de leurs conflits. Elles ne pourront vivre longtemps dépossédées de leurs âmes. Nous assistons sûrement à une accélération du temps, à l'irruption d'un autre univers mental, où les contradictions frontales seront atténuées et les schémas dialectiques ne seront plus en mesure de rendre compte de l'histoire telle qu'elle est. Dans la perspective d'un avenir, où les buts de la vie humaine seront partiellement profanes, tout en demeurant pour une part transcendants, les anciennes croyances ne pourront que réapparaître dans la vie historique.

Immédiatement, nous observons la fin provisoire de l'âge idéologique et de l'utilisation, bonne ou mauvaise, de celle-ci. Cela ne signifie point leur disparition définitive, car les utopies et les rêves réapparais-sent perpétuellement dans le siècle, et ils en constituent la trame imaginaire. Les sociétés développées ont refusé le fanatisme et le millénarisme, au profit d'une phase d'apaisement de leurs conflits. Elles ne pourront vivre longtemps dépossédées de leurs âmes. Nous assistons sûrement à une accélération du temps, à l'irruption d'un autre univers mental, où les contradictions frontales seront atténuées et les schémas dialectiques ne seront plus en mesure de rendre compte de l'histoire telle qu'elle est. Dans la perspective d'un avenir, où les buts de la vie humaine seront partiellement profanes, tout en demeurant pour une part transcendants, les anciennes croyances ne pourront que réapparaître dans la vie historique. Libéralisme et religions y apparaissent sous un regard nouveau. Le libéralisme est un corpus doctrinal qui ne prêche pas de certitudes et vit uniquement dans le présent. L'avenir éloigné le laisse insensible, l'histoire lui apparaît profane, le règne de la liberté dépend d'un projet et d'un pari, profondément individuels. Les conceptions, religieuses et libérales, ont toutefois un point commun. Elles fournissent une base pour résister aux tyrannies de l'histoire. Les premières, rappelant la critique permanente du monde et de la contingence, les autres, se référant aux ambitions et aux finalités de la vie humaine, perpétuellement relatives, insyndicales et arbitraires, plongées dans un univers réversible et incertain.

Libéralisme et religions y apparaissent sous un regard nouveau. Le libéralisme est un corpus doctrinal qui ne prêche pas de certitudes et vit uniquement dans le présent. L'avenir éloigné le laisse insensible, l'histoire lui apparaît profane, le règne de la liberté dépend d'un projet et d'un pari, profondément individuels. Les conceptions, religieuses et libérales, ont toutefois un point commun. Elles fournissent une base pour résister aux tyrannies de l'histoire. Les premières, rappelant la critique permanente du monde et de la contingence, les autres, se référant aux ambitions et aux finalités de la vie humaine, perpétuellement relatives, insyndicales et arbitraires, plongées dans un univers réversible et incertain.

Hinsichtlich der „Umvolkung“ oder des „Bevölkerungsaustausches“ sollte man darauf hinweisen, daß es dies immer schon gegeben hat und immer geben wird. Vor kurzem gab es mehrere kleine Bevölkerungs-Austauschaktionen im ehemaligen Jugoslawien, wobei viele Kroaten, muslimische Bosniaken und Serben in Bosnien ihre ehemaligen Wohnorte verlassen mußten. Vertreibung wäre hier ein besseres Wort für diese Aktion, da dieser Bevölkerungsaustausch in Ex-Jugoslawien mitten im Kriege stattgefunden hat.

Hinsichtlich der „Umvolkung“ oder des „Bevölkerungsaustausches“ sollte man darauf hinweisen, daß es dies immer schon gegeben hat und immer geben wird. Vor kurzem gab es mehrere kleine Bevölkerungs-Austauschaktionen im ehemaligen Jugoslawien, wobei viele Kroaten, muslimische Bosniaken und Serben in Bosnien ihre ehemaligen Wohnorte verlassen mußten. Vertreibung wäre hier ein besseres Wort für diese Aktion, da dieser Bevölkerungsaustausch in Ex-Jugoslawien mitten im Kriege stattgefunden hat. Deswegen ist jegliche Kritik an der Masseneinwanderung ohne eine vorhergehende Kritik am liberalen Handel bzw. am Kapitalismus sinnlos. Und umkehrt. Die kleinen kriminellen Migrantenschlepper, die meistens aus dem Balkan stammen, sind nur ein Abbild der großen Gutmenschen-Migrantenschlepper, die in unseren Regierungen sitzen. Auch unsere Politiker, ob sie in Brüssel oder in Berlin sitzen, befolgen nur die Regeln des freien Marktes.

Deswegen ist jegliche Kritik an der Masseneinwanderung ohne eine vorhergehende Kritik am liberalen Handel bzw. am Kapitalismus sinnlos. Und umkehrt. Die kleinen kriminellen Migrantenschlepper, die meistens aus dem Balkan stammen, sind nur ein Abbild der großen Gutmenschen-Migrantenschlepper, die in unseren Regierungen sitzen. Auch unsere Politiker, ob sie in Brüssel oder in Berlin sitzen, befolgen nur die Regeln des freien Marktes.  Natürlich könnte der heutige Bevölkerungsaustausch von jedem europäischen Staat jederzeit gestoppt oder auch rückgängig gemacht werden, solange Politiker Mut zur Macht haben, solange sie politische Entscheidungen treffen wollen, oder anders gesagt, solange sie die Entschlossenheit zeigen, den Zuzug der Migranten aufzuhalten.

Natürlich könnte der heutige Bevölkerungsaustausch von jedem europäischen Staat jederzeit gestoppt oder auch rückgängig gemacht werden, solange Politiker Mut zur Macht haben, solange sie politische Entscheidungen treffen wollen, oder anders gesagt, solange sie die Entschlossenheit zeigen, den Zuzug der Migranten aufzuhalten.

Demzufolge stellt sich die Frage, was bedeutet es heute, ein guter Europäer zu sein? Ist ein Bauer im ethnisch homogenen Rumänien oder Kroatien ein besserer Europäer, oder ist ein Nachkomme der dritten Generation eines Somaliers oder Maghrebiners, der in Berlin oder Paris wohnt, ein besserer Europäer?

Demzufolge stellt sich die Frage, was bedeutet es heute, ein guter Europäer zu sein? Ist ein Bauer im ethnisch homogenen Rumänien oder Kroatien ein besserer Europäer, oder ist ein Nachkomme der dritten Generation eines Somaliers oder Maghrebiners, der in Berlin oder Paris wohnt, ein besserer Europäer? Die einzige Waffe, sich gegen den heutigen Völkeraustausch zu wehren, liegt in der Wiedererweckung unseres biologisch-kulturellen Bewußtseins. Ansonsten werden wir weiterhin nur die hohlen Floskeln der christlichen, liberalen oder kommunistischen Multikulti-Ideologie wiederkäuen. So richtig es ist, die Antifa oder den Finanzkapitalismus anzuprangern, dürfen wir nicht vergessen, daß die christlichen Kirchen die eifrigsten Boten des großen Bevölkerungsaustauschs sind.

Die einzige Waffe, sich gegen den heutigen Völkeraustausch zu wehren, liegt in der Wiedererweckung unseres biologisch-kulturellen Bewußtseins. Ansonsten werden wir weiterhin nur die hohlen Floskeln der christlichen, liberalen oder kommunistischen Multikulti-Ideologie wiederkäuen. So richtig es ist, die Antifa oder den Finanzkapitalismus anzuprangern, dürfen wir nicht vergessen, daß die christlichen Kirchen die eifrigsten Boten des großen Bevölkerungsaustauschs sind.

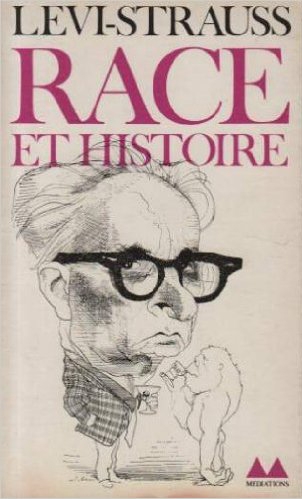

Je voudrai, à présent, citer une personnalité incontestable et incontournable, telle que celle de Claude Levi-Strauss: " Car, si notre démonstration est valable, il n'y a pas, il ne peut y avoir, une civilisation mondiale au sens absolu que l'on donne souvent à ce terme, puisque la civilisation implique la coexistence de cultures offrant elles le maximum de diversité, et consiste même en cette coexistence. La civilisation mondiale ne saurait être autre chose que la coalition, à l'échelle mondiale, de cultures préservant chacune son originalité". (Claude Levi-Strauss - "Races et Histoires").

Je voudrai, à présent, citer une personnalité incontestable et incontournable, telle que celle de Claude Levi-Strauss: " Car, si notre démonstration est valable, il n'y a pas, il ne peut y avoir, une civilisation mondiale au sens absolu que l'on donne souvent à ce terme, puisque la civilisation implique la coexistence de cultures offrant elles le maximum de diversité, et consiste même en cette coexistence. La civilisation mondiale ne saurait être autre chose que la coalition, à l'échelle mondiale, de cultures préservant chacune son originalité". (Claude Levi-Strauss - "Races et Histoires").

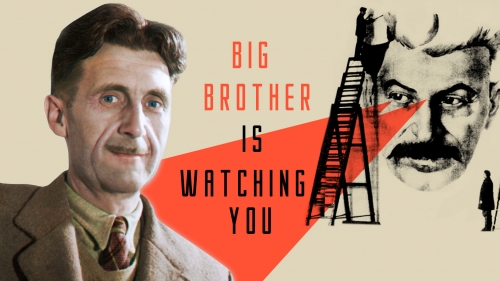

N’oublions pas non plus le rôle de certains groupuscules étudiants associés à l’ultragauche ou à certaines franges extrêmes de « l’antiracisme » ou du « féminisme » qui entendent encadrer la parole sur les campus, en distinguant ceux qui ont le droit de s’exprimer et ceux qui ne l’ont pas. De leur point de vue, la liberté d’expression n’est qu’une ruse « conservatrice » servant à légitimer l’expression de propos haineux ou discriminatoires — c’est ainsi qu’ils ont tendance à se représenter tous les discours qui s’opposent à eux frontalement. Ces groupuscules au comportement milicien n’hésitent pas à verser dans la violence, et pas que verbale, et cela, avec la complaisance d’une partie du corps professoral, qui s’enthousiasme de cette lutte contre les « réactionnaires » et autres vilains. Ils entrainent avec eux des étudiants emportés par une forme d’hystérie collective dont les manifestations font penser à la scène des deux minutes de la haine chez Orwell. Nous pourrions parler d’ivresse idéologique : des idées trop vite ingérées et mal comprises montent à la tête de jeunes personnes qui se transforment en vrais fanatiques.

N’oublions pas non plus le rôle de certains groupuscules étudiants associés à l’ultragauche ou à certaines franges extrêmes de « l’antiracisme » ou du « féminisme » qui entendent encadrer la parole sur les campus, en distinguant ceux qui ont le droit de s’exprimer et ceux qui ne l’ont pas. De leur point de vue, la liberté d’expression n’est qu’une ruse « conservatrice » servant à légitimer l’expression de propos haineux ou discriminatoires — c’est ainsi qu’ils ont tendance à se représenter tous les discours qui s’opposent à eux frontalement. Ces groupuscules au comportement milicien n’hésitent pas à verser dans la violence, et pas que verbale, et cela, avec la complaisance d’une partie du corps professoral, qui s’enthousiasme de cette lutte contre les « réactionnaires » et autres vilains. Ils entrainent avec eux des étudiants emportés par une forme d’hystérie collective dont les manifestations font penser à la scène des deux minutes de la haine chez Orwell. Nous pourrions parler d’ivresse idéologique : des idées trop vite ingérées et mal comprises montent à la tête de jeunes personnes qui se transforment en vrais fanatiques. Campus Vox :

Campus Vox :  Mathieu Bock-Côté : L’université française était-elle autant épargnée qu’on l’a dit ? Une chose est certaine, la vie intellectuelle française n’était pas épargnée par le sectarisme. Il suffirait de se rappeler l’histoire de l’hégémonie idéologique du marxisme, d’abord, puis du post-marxisme, dans la deuxième moitié du XXe siècle, pour s’en convaincre. Cela dit, il est vrai que la France est aujourd’hui victime d’une forme de colonisation idéologique américaine — on le voit par exemple avec l’application systématique sur la situation des banlieues issues de l’immigration de grilles d’analyse élaborées pour penser la situation des Noirs américains, comme si les deux étaient comparables ou interchangeables. La sociologie décoloniale s’autorise cette analyse dans la mesure où elle racialise les rapports sociaux, évidemment.

Mathieu Bock-Côté : L’université française était-elle autant épargnée qu’on l’a dit ? Une chose est certaine, la vie intellectuelle française n’était pas épargnée par le sectarisme. Il suffirait de se rappeler l’histoire de l’hégémonie idéologique du marxisme, d’abord, puis du post-marxisme, dans la deuxième moitié du XXe siècle, pour s’en convaincre. Cela dit, il est vrai que la France est aujourd’hui victime d’une forme de colonisation idéologique américaine — on le voit par exemple avec l’application systématique sur la situation des banlieues issues de l’immigration de grilles d’analyse élaborées pour penser la situation des Noirs américains, comme si les deux étaient comparables ou interchangeables. La sociologie décoloniale s’autorise cette analyse dans la mesure où elle racialise les rapports sociaux, évidemment. Mathieu Bock-Côté : Cela fait des années que ceux qu’on appelle les conservateurs (mais pas seulement eux) tiennent tête au politiquement correct et il est heureux de voir qu’ils ont du renfort. Jacques Parizeau, l’ancien Premier ministre du Québec, disait, à propos de ceux qui rejoignaient le mouvement indépendantiste : « que le dernier entré laisse la porte ouverte s’il vous plaît ». Les conservateurs peuvent dire la même chose dans leur combat contre le régime diversitaire. L’enjeu est historique : il s’agit de préserver aujourd’hui la possibilité même du débat public en rappelant que le pluralisme intellectuel ne consiste pas à diverger dans l’interprétation d’un même dogme, mais dans la capacité de faire débattre des visions fondamentalement contradictoires qui reconnaissent néanmoins mutuellement leur légitimité. Ce n’est qu’ainsi qu’on pourra tenir tête à la tyrannie des offensés qui entendent soumettre la vie publique à leur sensibilité, et qui souhaitent transformer tout ce qui les indigne en blasphème. La France n’est pas épargnée par le politiquement correct, mais elle y résiste, en bonne partie, justement, parce qu’elle dispose d’un espace intellectuel autonome d’un système universitaire idéologiquement sclérosé. On peut croire aussi que la culture du débat au cœur de l’espace public français contribue à cette résistance. C’est en puisant dans leur propre culture que les Français trouveront la force et les moyens de résister au politiquement correct

Mathieu Bock-Côté : Cela fait des années que ceux qu’on appelle les conservateurs (mais pas seulement eux) tiennent tête au politiquement correct et il est heureux de voir qu’ils ont du renfort. Jacques Parizeau, l’ancien Premier ministre du Québec, disait, à propos de ceux qui rejoignaient le mouvement indépendantiste : « que le dernier entré laisse la porte ouverte s’il vous plaît ». Les conservateurs peuvent dire la même chose dans leur combat contre le régime diversitaire. L’enjeu est historique : il s’agit de préserver aujourd’hui la possibilité même du débat public en rappelant que le pluralisme intellectuel ne consiste pas à diverger dans l’interprétation d’un même dogme, mais dans la capacité de faire débattre des visions fondamentalement contradictoires qui reconnaissent néanmoins mutuellement leur légitimité. Ce n’est qu’ainsi qu’on pourra tenir tête à la tyrannie des offensés qui entendent soumettre la vie publique à leur sensibilité, et qui souhaitent transformer tout ce qui les indigne en blasphème. La France n’est pas épargnée par le politiquement correct, mais elle y résiste, en bonne partie, justement, parce qu’elle dispose d’un espace intellectuel autonome d’un système universitaire idéologiquement sclérosé. On peut croire aussi que la culture du débat au cœur de l’espace public français contribue à cette résistance. C’est en puisant dans leur propre culture que les Français trouveront la force et les moyens de résister au politiquement correct

Comments like these have caused a

Comments like these have caused a  And that is coming from a group of self-identified anarchists! We also have the statements of literal ecofascists, such as the late and venerable Pentti Linkola, whose observations of mass man’s destructive nature famously led him to write: “If there were a button I could press, I would sacrifice myself without hesitating, if it meant millions of people would die.” Rather than mass die-offs, however, his preference was for the complete abolition of liberal democracy and the institution of a strong centralized government with “tireless control of citizens,” which could enact the controversial measures necessary to reverse human-inflicted environmental damage.

And that is coming from a group of self-identified anarchists! We also have the statements of literal ecofascists, such as the late and venerable Pentti Linkola, whose observations of mass man’s destructive nature famously led him to write: “If there were a button I could press, I would sacrifice myself without hesitating, if it meant millions of people would die.” Rather than mass die-offs, however, his preference was for the complete abolition of liberal democracy and the institution of a strong centralized government with “tireless control of citizens,” which could enact the controversial measures necessary to reverse human-inflicted environmental damage.

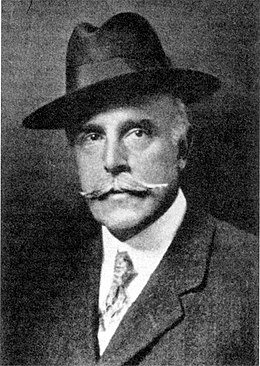

The environmental dimensions of the immigration debate are less well-known. The link between wilderness preservation and nativism was established by Madison Grant in the 1920s, but disappeared in the latter half of the 20th century. This is because, since the 1970s, the environmental movement has been almost completely dominated by leftists who have pushed this question to the wayside for purely ideological reasons.

The environmental dimensions of the immigration debate are less well-known. The link between wilderness preservation and nativism was established by Madison Grant in the 1920s, but disappeared in the latter half of the 20th century. This is because, since the 1970s, the environmental movement has been almost completely dominated by leftists who have pushed this question to the wayside for purely ideological reasons.